Scopes & Scapes

Southern Exposure presents four solo exhibitions and projects by: Mike Lai, Genevieve Quick, Lacey Jane Roberts and Andy Vogt.

Genevieve Quick is a San Francisco-based artist whose work addresses the history of image making and landscape with a particular focus on the mechanics of visualization. While referencing optical devices from the Victorian era as well as those from the end of the 19th century, Quick’s sculptures appear nostalgic and at the same time suggestive of retro-futuristic and science fiction worlds. For her solo exhibition at Southern Exposure, Quick presents Scopes and Scapes, a combination of carefully crafted sculptures and drawings exploring past and future ways of looking.

Essay by Valerie Imus

I sometimes wonder why science fiction often seems to feature references to outdated technologies and past genres—noirish voice-overs, rotary phones, cowboys. Is it to suggest the absurdity of fantasizing about the future’s cure-all innovations, or to make us feel more at home in the unknown by depicting history as cyclical? Genevieve Quick’s retro-futurist optical devices evoke that uneasy sense of nostalgia, absurdity, and simultaneous wonderment.

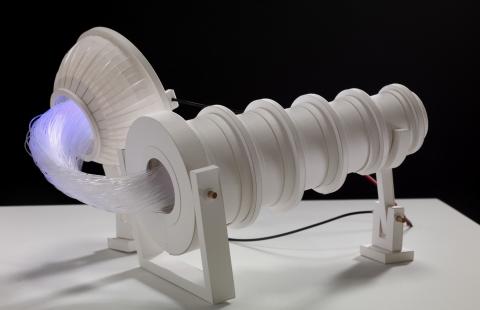

Quick creates visual prostheses based on an outmoded mechanics of looking. Painstakingly constructed entirely from white paper and foam core, these intricately fabricated, delicate ocular instruments are both conceptual and actual models of the observation process based on the technology of a camera obscura. On first glance, her sculpture MacroScopicSpace appears to be a pristine, white camera with an extended lens on a tripod, but its construction is far more complex: light reflecting from a tiny, lone tree on a paper island bounces to a series of mirrors and lenses, to be projected on a sheet of acetate at the opposite side of the device—a softened image of a romantic and melancholy tableau.

As devices for viewing, Quick’s sculptures often function as extensions of the observer’s body. The TPP Unit (Tellurian Projection Pack), her shoulder-harnessed viewing mechanism—portable and ready for fieldwork—looks like a futuristic jet pack for the intrepid Victorian explorer of pastoral terrain. The practical size and functionality implies usability, but the ephemerality and absurd redundancy of purpose renders the device fantastical and impractical as an actual tool. Blocking the position of one eye is a tube with a small aperture that allows the obscured scene to bounce through a series of four lenses and ultimately be projected onto a small screen on the backpack of the wearer. The device turns the process of perception inside out and makes mere observation into an absurdly elaborate and meandering experience; moving the scene out of the wearer’s line of vision and instead revealing it to someone who might be standing behind effectively allows the wearer to bear her own perspective on her back.

In recasting the camera obscura from a darkened room to an object strapped to the observer’s body, Quick creates a personal theater of observation, or a portable mind’s-eye cinema. This dual planar conceptualization of the observer and re-envisioned image of the observed parallels both a proto-modern visualization model and current high-tech disembodied methods of observation, used for instance in endoscopic surgery or space exploration. This distanced and indirect relationship to an observed landscape also models a contemporary urban disconnection from the natural world. Camera obscuras were popularized during the 17th and 18th centuries, when landscape was commonly seen as something available for exploration, analysis, and domination by a specifically formulated subject. One can argue that the modern interest in space exploration is an extension of this perspective.

The Hubble, like the camera obscura, is a tool used to frame and more closely examine the scenic, to transform the natural world into something that can be easily contemplated and understood. The Hubble telescope and Viking spacecraft are extrapolated forms of visual prostheses, so far removed as to be impossible for us to look through—or even to see—but enabling us to look at images beyond our natural scope. Because images of these modern instruments are so hard to come by, Quick’s negative drawings of the Hubble and Viking1 are based on downloaded images of models and CGI representations.

These devices, and our challenges in conceptualizing them, inject increasing distance between the observer, what’s being observed, and the tool enabling that observation, further abstracting the process of visualization. The proliferation of photographic equipment and its expanded capability to produce images of objects infinitesimally small or far away has shifted the ways that we envision the world, while promising to forge a more profound relationship to the truth. Quick playfully ponders the romance and nostalgia within this notion by simultaneously reconstructing past and current mechanics of looking and making our processes of revisualization more palpable.