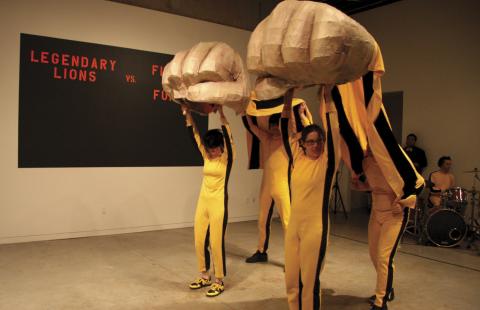

The Legendary Lions vs. the Fists of Fury

Join Southern Exposure and Mike Lai for The Legendary Lions vs. the Fists of Fury, a dance-off competition between traditional Chinese lion dancers and Bruce Lee's larger than life sized fists. A contest between the physical performance of traditional, authentic Kung Fu and the showmanship and special effects of contemporary, filmic Kung Fu, the event will feature five sets of battles. M.C. Julian Mocine-McQueen and local judges from the fields of art, Kung Fu and dance along with the audience will determine the winners.

The event features Leung's White Crane Dragon and Lion Dance Association, Ben's Shaolin Kung Fu Lion Dance Team, the Fist of Fury Dance Crew, Scratch DJ and drummer Skins and Needles and MC Julian Mocine-McQueen.

Come celebrate the Chinese New Year with this epic battle!

Essay by Weston Teruya

Chinese lion dancers bounce across the floor with staccato movements to the beat of drums and cymbal crashes. After sizing up the performance, dancers draped in oversized, disembodied replicas of Bruce Lee’s fists of fury face off against the lion. The sharp response of a turntable needle at a DJ’s fingers accent their array of dynamic moves. The showdown, Mike Lai’s performance piece titled The Legendary Lions Versus the Fists of Fury, matches the acrobatic athleticism of a traditional lion dance against the analog approximations of martial arts movie special effects used by the Bruce Lee dance crew. This kinetic scene, orchestrated by Lai for his solo show at Southern Exposure, seems equal parts America’s Best Dance Crew spectacle, climactic battle between martial arts masters, and nod to the celebratory blessing typically signified by a lion dance. But these points in his referential constellation are only some of the cultural markers he has been drawing down for years as part of his artistic practice. His recombinant performances, centering on the artist (often in the guise of Lee), use Lee’s pop culture versatility to playfully suggest the flexible possibilities of remixed identities.

Lai has a particular affinity for Lee in his Game of Death mode: tightly sheathed in a yellow tracksuit with black stripes running up the sides. In The Legendary Lions Versus the Fists of Fury, the hallmark contrasting stripes immediately identify the disembodied dancing fists as Lee’s. This is Lee from his showdown against basketball legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar, a cinematic scene highlighting Lee’s own cross-cultural resonance. This is also Lee after his tragic death mid–film shoot, in a performance completed by a motley mix of stand-ins, recut stock footage, and his face crudely pasted over some poor wannabe’s unseen mug; his own film emphasizing that fissure between Lee the person and Lee the immortal persona, a character to be assumed by others.

Over time, Lee’s has become an outsized, fantastical identity. His tracksuit, as Lai has suggested, is a superhero cape—hypercolor drag that combines assumed identity and masculine desire. Fans from Ultimate Fighting Championship combatants to the Asiaphiles of the Wu-Tang Clan have paid their respects to Lee. Yet as desire is often intertwined with repulsion, the label “bruce lee” also can be a racial invective. For East Asian American men with similarly lithe body types, the name can be a playground dismissal—a suggestion of chop-socky cartoonishness and broken English. For Lai, being called “bruce lee” by classmates on arrival at high school in the United States stirred mixed feelings: on one hand, the name flattened him, reducing his identity to a celluloid ghost; on the other, it seemed heroic to be viewed as akin to the original Asian stud.

Lai finds ways to both embrace and combat this conflation. With each new cultural iteration of Lee that he imagines, he flips any singular reading of the legendary figure. In a small 2005 performance, Lai took on the image of “The Bride” as performed by Uma Thurman in Kill Bill, vamping in a men’s bathroom mirror in a Lee-inspired tracksuit. Using a cross-racial, gender-bending, temporal collapse, he complicated the fixed premises on which the original icon was built.

For his performance at Southern Exposure, Lai turns to an intracultural dialogue, arranging a battle between living tradition and filmic showmanship. The conflict between older and newer guards arises as a familiar trope in the films Lai references. In Legendary Lions, the competitive pairing leaves open the possibility for triumph and failure for either group. By raising the question of tradition in his larger grouping of referents, Lai undercuts the bedrock of cultural essentialisms, suggesting that their existence is as potentially momentary as any other point of connection. No matter how fierce the dance-off, Lai reminds us of the generative possibilities of a cultural representation like Lee and that they can also be a source of connection, wonder, and play.